Hey, Y’Know What Movie Is Not Overrated? ‘Citizen Kane’

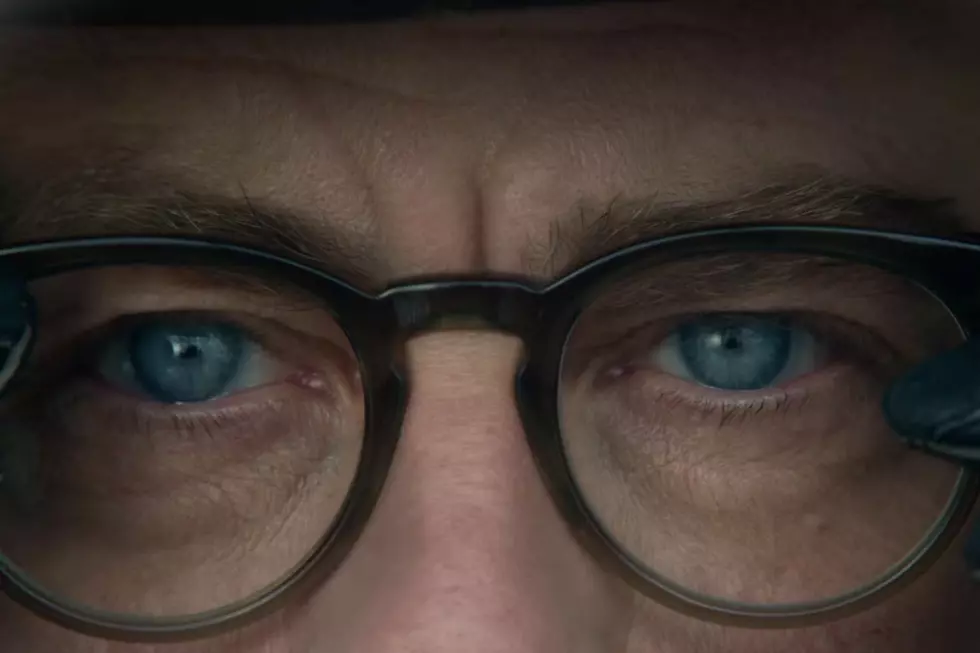

There are many reasons to anticipate the release of Mank. It’s the first film from director David Fincher in six years, and his first in black and white. It’s a historical drama, and both of his previous historical dramas — Zodiac and The Social Network — are masterpieces. It also explores the world of Hollywood in the early 1940s, a fascinating period, and the making of one of the most famous films in history, Citizen Kane.

There’s also at least one big reason to dread the release of Mank. Someone — maybe several people, perhaps a lot of people, but at least someone — will use Mank as an excuse to write a hot take about how Citizen Kane is actually overrated, dated, uninteresting, and above all, bad. This is how the internet works these days. One of the most reliable ways for a culture writer to get clicks is to find a consensus favorite, pick it apart, and wait for the hate-shares to roll in.

Reconsidering the canon and its most sacred cows is a valid approach to criticism, and important work in some cases. Some classics don’t age well. Not Citizen Kane, though. It still looks impressive almost 80 years after its release, and speaks more clearly about politics in 2020 than basically any movie made in the last decade.

Kane’s bold visual style and formal innovations are legendary. Any film student can recite them from memory: The use of “deep focus” photography by cinematographer Gregg Toland; his expert deployment of mattes and dissolves and cross-fades; the mimicry of the formal language of documentaries for the “News on the March” sequence; camera placements so low to the ground that Toland and director Orson Welles had to drill through the floor of the studio to achieve them.

Few of these techniques were invented by Welles and Toland on Citizen Kane; their genius came in combining all these different ideas in order to tell a structurally complex story about the rise and fall of an American newspaper tycoon. Even if time and the adoption of many of its tricks by other films make Kane look less groundbreaking now than it was in its day, it’s still full of uncommonly beautiful images. Just to cite a few:

Ironically, critics sometimes hold up these indelible frames as evidence that Citizen Kane is nothing more than a showcase of empty, emotionless techniques. For years, I’ve read dismissals of Kane as a boring, unemotional story about an unrelatable rich guy who inherited an enormous fortune and squandered it on a newspaper empire and vanity political campaigns.

Whatever element of subjective opinion plays into these assessments, it’s impossible to deny that Citizen Kane possesses renewed relevance in the era of modern American politics dominated by Donald Trump, one of the most Kanesian figures in American history. In fact, despite a steady stream of documentaries, fictional shows like The Comey Rule and Our Cartoon President, and countless impressions on social media, I’m not sure any piece of popular culture made in the last four years better understands Trump than Citizen Kane — even though it was released five years before Trump was born.

Welles and co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz (Mank!) drew inspiration for their screenplay from the life of William Randolph Hearst, an enormously powerful newspaper publisher who lived his final years in a sprawling estate called San Simeon that, like Kane’s own Xanadu, was never finished. Many elements of Welles and Mankiewicz’s Charles Foster Kane parallel Hearst, including their failed bids to become governor of New York, their use of yellow journalism to help push the United States into the Spanish-American War, and their disastrous marriages following affairs with young women from the world of entertainment.

While the details come from Hearst, Kane’s deeper emotional truths all sound like Trump, particularly in the sequence narrated by Kane’s old friend Jed Leland (Joseph Cotton), who chronicles Kane’s failed political career and the destruction of his first marriage. Although early sequences in Citizen Kane feature characters labeling Kane a “Communist” and a “fascist” — a deliberate contradiction designed to show how the different characters in the film have different perspectives of the title character and his vague politics — Leland’s portion of the film suggest Kane was actually a populist, leveraging working-class resentment for his own political gain. In his big campaign speech, he even calls for the prosecution of his political enemies.

Kane’s run for the governorship gets derailed by the revelation of an affair with a singer named Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore). Faced with a humiliating loss after victory seemed all but assured, Kane’s newspaper publishes a report claiming “FRAUD AT POLLS!” rather than conceding defeat:

In the sequences that bookend these flashbacks, Leland offers some compelling insights into Kane’s psychology. Kane, he says...

...had a generous mind, I don’t suppose anybody ever had so many opinions. But he never believed in anything except Charlie Kane. He never had a conviction except Charlie Kane in his life.

Abandoned at a young age by his parents — who left him in the care of a bank so he could be “properly” raised to administer the family fortune — Leland says everything Kane did was motivated by his quest to feel love. “That's all he ever wanted out of life... was love,” he explains. “That's the tragedy of Charles Foster Kane. You see, he just didn't have any to give.” Confronting Kane on the night of his defeat in the governor’s race, Leland insists he failed because he only entered the race for that same reason; his quest for “love on his own terms.” The camera, placed at the characters’ ankles, follows Kane as he wanders through the empty newspaper office. The low angle, which gives figures a towering presence and is typically used to suggest a character’s strength, ironically shows this hugely powerful man laid low by his own ego. Kane grabs a glass and toasts his friend: “To love of my own terms. Those are the only terms anybody ever knows - his own.”

You can decide for yourself whether any of these descriptions sound like our President. However, we do know this about Trump: He is a fan of Citizen Kane. In fact, in several interviews, he called it his favorite film ever. He once even mused about its resonance for documentarian Errol Morris:

Whether or not it’s his favorite film, Trump’s comments make it clear he doesn’t quite grasp the totality of Citizen Kane’s message. (For one thing, the film is definitely not suggesting that the root of Kane’s problems was he needed to “get [himself] a different woman.”) We shouldn’t hold that against Welles and Mankiewicz. (Mank!) Trump simply loves Kane on his own terms — the only terms anybody ever knows.

Citizen Kane is currently available on HBO Max.

Gallery — The Silliest Sequel Subtitles in History:

More From Rock 104.1